Native American Tribes: The Ababco

Published on December 18, 2025

Published on Wealthy Affiliate — a platform for building real online businesses with modern training and AI.

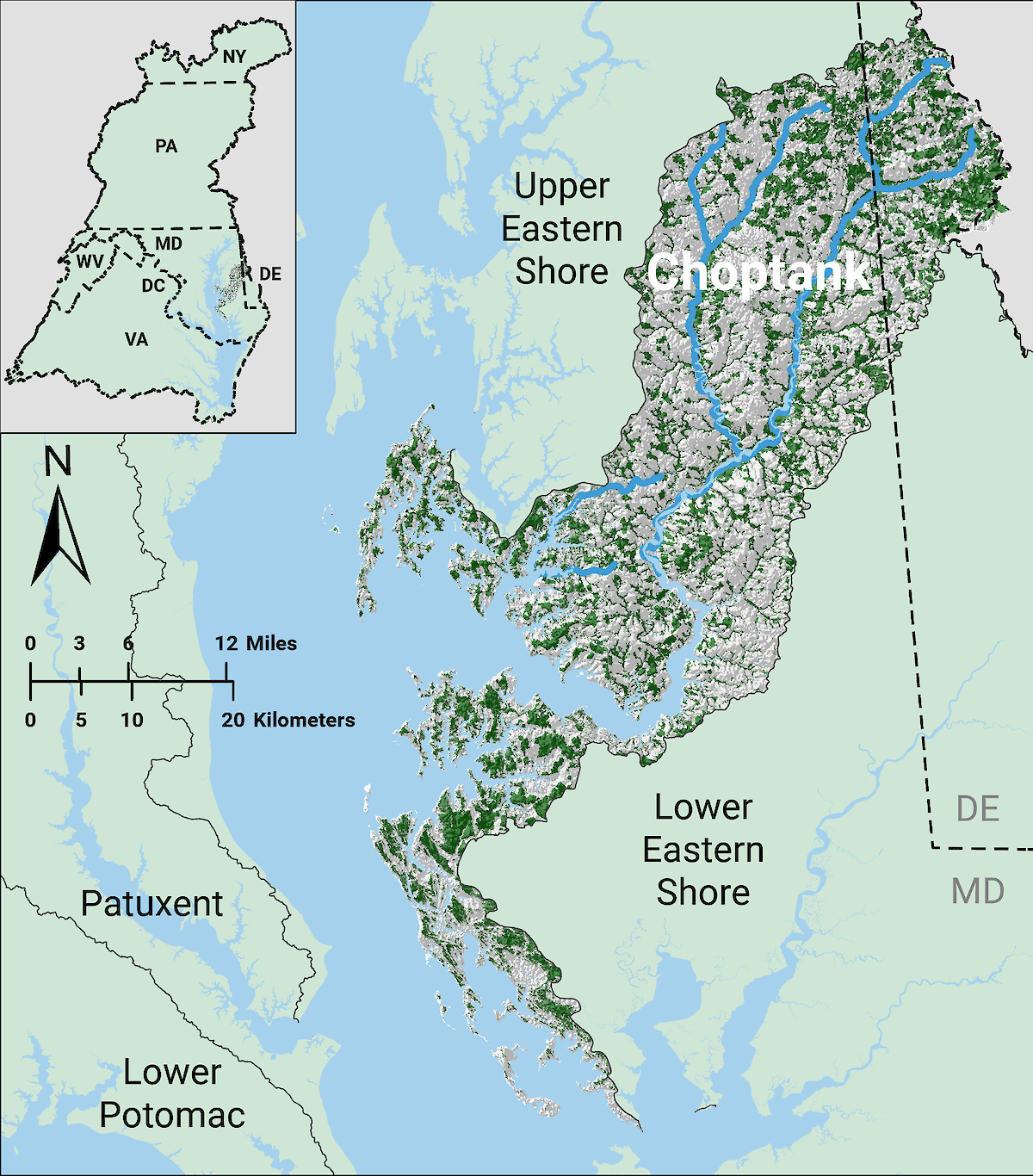

The Ababco Indian tribe is an eastern Algonquian tribe or sub-tribe that initially lived on the Choptank River in Maryland when first encountered by Europeans.

https://www.lake-art.com/cdn/shop/files/md-choptank-river-dorchester-talbot-3D-wood-map-255.png?v=1747067855" width="410" height="410" data-image-anchor="">

https://www.lake-art.com/cdn/shop/files/md-choptank-river-dorchester-talbot-3D-wood-map-255.png?v=1747067855" width="410" height="410" data-image-anchor="">

https://www.hmdb.org/Photos9/900/Photo900825.jpg" width="inherit" height="inherit" data-image-anchor="">

https://www.hmdb.org/Photos9/900/Photo900825.jpg" width="inherit" height="inherit" data-image-anchor=""> https://ecoreportcard.org/site/assets/files/2236/choptank_group_annotation_stream_and_river_update_final_v2_edited.1200x0.png" width="inherit" height="inherit" data-image-anchor="">The Ababco name appears in 17th-century Maryland records as a chief, town-name, or band closely associated with the Choptank people — Eastern Algonquian speakers who lived on the lower Choptank River (modern Dorchester, Talbot, and nearby counties). Their lifeways were river-centered: villages on creeks and necks, mixed corn-farming and abundant fisheries, dugout/wooden watercraft, basketry and pottery traditions, and complex kin and political ties with neighboring Nanticoke groups. Colonial records show the Maryland Assembly created a Choptank reservation in 1669; the legislative language and later records mention Ababco as a named leader. Archaeology (shell middens, site surveys) and modern tribal descendants (Nause-Waiwash, Nanticoke) help complete the picture.

https://ecoreportcard.org/site/assets/files/2236/choptank_group_annotation_stream_and_river_update_final_v2_edited.1200x0.png" width="inherit" height="inherit" data-image-anchor="">The Ababco name appears in 17th-century Maryland records as a chief, town-name, or band closely associated with the Choptank people — Eastern Algonquian speakers who lived on the lower Choptank River (modern Dorchester, Talbot, and nearby counties). Their lifeways were river-centered: villages on creeks and necks, mixed corn-farming and abundant fisheries, dugout/wooden watercraft, basketry and pottery traditions, and complex kin and political ties with neighboring Nanticoke groups. Colonial records show the Maryland Assembly created a Choptank reservation in 1669; the legislative language and later records mention Ababco as a named leader. Archaeology (shell middens, site surveys) and modern tribal descendants (Nause-Waiwash, Nanticoke) help complete the picture.

Mayis Indigenous Records+2Maryland State Archives+2

Land, waters, and why the river shaped everything

The lower Choptank River is tidal and branching: marshes, creeks, wooded necks, and rich brackish wetlands. For the Ababco/Choptank this meant:

- Travel and trade by canoe — waterways were the highways connecting villages, fisheries, and trading partners across the Delmarva.

- Mixed-resource productivity — reliable corn/bean/squash fields plus abundant fish, waterfowl, turtles and shellfish (including oysters/clams) that created large shell middens at many sites. Archaeologists now interpret middens as evidence of long-term, complex aquatic management and seasonal scheduling of harvests. Hakai Magazine+1

- A living landscape — tidal marsh plants, riverine forests, and freshwater creeks provided materials for baskets, mats, cordage, and house construction. DNREC Documents

Settlement, housing, and village organization

- Village footprint. Villages clustered on raised ground or “necks” above tidal marshes, often along small creeks where fields, woods, and water were all nearby. The historic Choptank reservation later recorded at Locust Neck is one such locality. Maryland.gov Enterprise Agency Template

- Houses and community spaces. Wigwam-style framed and thatched houses (mobile/repairable), storage pits for corn, ceremonial/communal spaces, and cordage and canoe work areas were typical of regional Eastern Algonquian village plans. Wikipedia

Foodways and economy — seasonality and balance

- Agriculture: Maize (corn), beans and squash fields near villages provided stored calories for winter. These “garden” systems were maintained with slash-and-burn clearance and managed soils. Jefpat

- Fishing & shellfish: Seasonal fisheries — weirs, nets, hooks, spear-fishing, and shellfish gathering — supplied protein. Shell middens (archaeological deposits of discarded shells) show repeated generations of shellfish use and specialized knowledge of tidal cycles. Hakai Magazine+1

- Hunting & wild resources: Deer, turkey, smaller mammals, wild nuts (oak mast), and freshwater plants supplemented diets.

- Craft economies & exchange: Pottery, basketry, bone and stone tools circulated locally and regionally; rivers carried items and ideas to neighboring Algonquian-speaking groups. Mayis Indigenous Records+1

Political organization, identity, and the name “Ababco”

- Ababco in colonial records. “Ababco” appears in Maryland colonial proceedings as a named chief (a werewance) or place-name connected to the Choptank people. These records sometimes use Ababco and Choptank interchangeably in legal and council minutes — a common colonial shorthand when recording Indigenous interlocutors. Mayis Indigenous Records+1

- Regional ties. The Choptank were closely affiliated with the larger Nanticoke polity and other Eastern Shore groups through marriage, political confederation, and trade. National Park Service

Treaties, reservation (1669), and a contemporary colonial quote

Maryland’s colonial government set aside a reservation for the Choptank in 1669. The language used in Assembly proceedings explicitly framed the gesture as politically motivated: to maintain peaceful relations with Indigenous neighbors. A representative excerpt appearing in the colonial records reads (emphasis added):

Ready to put this into action?

Start your free journey today — no credit card required.

“for the continuation of peace with, and protection of, our neighbours and confederates, the Indians on Choptank River…” Maryland State Archives+1

That 1669 action resulted in lands near Locust Neck being set aside as the Choptank (often recorded alongside Ababco) reservation; the reservation persisted in records into the 18th century, though colonists’ pressure and later sales eroded Indigenous landholding and community life over time. Maryland State Arts Council+1

Contact, disease, and demographic change

- Disease: Epidemics (smallpox, influenza, other Eurasian diseases) decimated coastal tribal populations in the 17th century; demographic collapse reshaped leadership, alliances, and ability to defend or hold land.

- Land loss & dependency: Settler land claims, legal transactions often disadvantaging Indigenous sellers, and economic shifts (tobacco, grain, livestock) led to dispossession. Although the Choptank reservation was a rare fee-simple grant, it did not prevent gradual loss through leases, sales, and colonial pressures. Maryland State Arts Council+1

What archaeology adds (and recent projects)

- Shell middens & resilient practices. Archaeological studies across Delmarva show that shell middens are not simply “trash”: they preserve plant and animal assemblages and even unique plant communities. Research suggests Indigenous people managed oysters and other shellfish with sustainable long-term strategies. Hakai Magazine+1

- Site surveys & rescue archaeology. MD Historical Trust site forms and recent Phase II/III reports document shell middens and village loci in the Choptank drainage (e.g., Holland Point and other Dorchester County sites), some eroding under modern sea-level and development pressures. These reports are critical for mapping pre-contact settlement and for preservation. Jefpat+1

- New fieldwork. University-led field schools (Washington College) and cooperative projects are actively re-examining the CHOPTANK watershed to better understand river-centered lifeways. washcoll.edu+1

Maps & illustrated timeline (text + images)

Maps provided here

(Images at top of this post)

- Choptank River shoreline/watershed map — shows the river branching into tidal creeks and the wider Chesapeake. Useful for understanding village siting.

- Historic/nautical and local maps — good for overlaying colonial-era place names (Locust Neck, Secretary Creek) onto modern maps.

- Choptank Reservation marker photo — locates the modern historical marker near Cambridge/Locust Neck; useful for site visits and commemoration contexts.

Illustrated timeline

- Before ca. 1600s — Millennia of Indigenous occupation; shell middens and village sites forming across Delmarva. (Archaeological record.) DNREC Documents

- 1608–1620s — Early European contact in the Chesapeake; initial trade and intermittent conflict. (Context: Captain John Smith & early explorers for the region.) nanticokeindians.org

- 1669 — Maryland General Assembly creates the Choptank reservation: legislative language framed “for the continuation of peace with, and protection of, our neighbors and confederates, the Indians on Choptank River …” — primary legislative phrasing recorded in the Proceedings. (Place this as a major timeline node with the quoted line and a citation.) Maryland State Archives+1

- Late 17th – 18th centuries — Continued legal appearances of Ababco and Choptank leaders in Council proceedings; pressure on lands increases; some reservation confirmations appear in later colonial documents (e.g., deeds, council minutes). Mayis Indigenous Records+1

- Late 1700s – early 1800s — Shrinking village populations; final historic village at Locust Neck declines by late 18th century into early 19th (records note last known Choptank town occupancy into the 1790s/early 1800s). National Park Service+1

- 20th–21st century — Archaeological surveys, shell midden research, and cultural revitalization by descendant communities (Nause-Waiwash, Nanticoke) and public history efforts such as roadside markers and museum exhibits. National Park Service

Interview-style sidebar: who to contact, and suggested questions

Below is a compact “who to call/email” list and suggested interview questions you can use in a sidebar or as outreach templates.

Local scholars & archaeology programs

- Washington College — Department of Anthropology & Archaeology

Why: active fieldwork on the Choptank watershed; field school and artifact labs.

Contact: Dr. Julie G. Markin, Chair & Director of Washington College Archaeology — department pages list faculty contacts and field school info. washcoll.edu+1

Suggested questions: - What recent archaeological evidence has most changed our view of Choptank lifeways?

- Can you describe a site (artifact, midden, context) that tells a vivid story about daily life along the river?

- How can journalists and local historians responsibly access site information without endangering locations?

- Maryland Historical Trust (MHT)

Why: central repository for Maryland archaeological site forms (MIHP), permits, and public outreach.

Contact: MHT archaeology pages and staff directory (Medusa/MIHP help: Jennifer Cosham; general contacts listed online). Maryland Historical Trust+1

Suggested questions: - What MHT resources/documents best document the 1669 reservation and Locust Neck area?

- What protections are in place (or lacking) for shell middens and low-lying archaeological sites on the Eastern Shore?

Tribal & descendant community contacts

- Nause-Waiwash Band of Indians (Dorchester/Cambridge area)

Why: community of descendants whose members trace lineage and stewardship to Choptank/Nanticoke ancestors and who lead cultural events and education. Local leaders are regularly active in public history and powwow events. (Chief Donna ‘Wolf Mother’ Abbott is a current public leader.) dorchesterchambermd.chambermaster.com+1

Suggested questions: - What stories passed down in your community best convey Choptank/Ababco life before 1700?

- How would you like local media and historians to present reservation and land history?

- Nanticoke Indian Tribe & Museum (Millsboro, DE) — tribe-run museum with exhibits and education programs. Good for artifacts, language, and long-term cultural continuity. nanticokeindians.org+1

Footnotes & selected primary sources (quick reference)

- Maryland State Archives — Mayis index: entries for “Ababco” in the Proceedings of the General Assembly and Proceedings of the Council (1669 and later). This index lists specific page citations for the 1669 proceedings and later council minutes that name Ababco and related persons. Mayis Indigenous Records

- Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly (Archives of Maryland, Vol. 2) — colonial language on the Choptank reservation (quoted phrasing appears in the volume). See the Archives of Maryland entry: “Then was read the Act for Continuance of peace with & Protection of our Neighbours & Confederate Indians in Choptank River.” Maryland State Archives+1

- Maryland Historical Trust site reports and Phase II/III forms documenting shell middens and Choptank River sites (sample forms & PDFs). See MHT site syntheses for Dorchester sites and site numbers (e.g., 18DO393; 18DO220). MHT Apps+1

- Archaeology and environmental reporting on shell middens and oyster management in the Chesapeake (Hakai Magazine summary of scientific work). Useful for visual and interpretive framing of midden use. Hakai Magazine

- Modern recognition & public commemoration: Maryland Department of Transportation / Maryland Historical Trust reporting on the Choptank Indian Reservation historical marker and Nause-Waiwash ceremonies (2024 marker unveiling coverage). Maryland.gov Enterprise Agency Template

Share this insight

This conversation is happening inside the community.

Join free to continue it.The Internet Changed. Now It Is Time to Build Differently.

If this article resonated, the next step is learning how to apply it. Inside Wealthy Affiliate, we break this down into practical steps you can use to build a real online business.

No credit card. Instant access.